Model Railroader posted a freebie on the top ten considerations for operations on a layout. It was originally published in 2002, but provides an interesting basis for a discussion of operations.

10 ways to foster operation on your layout by Tony Koester

-

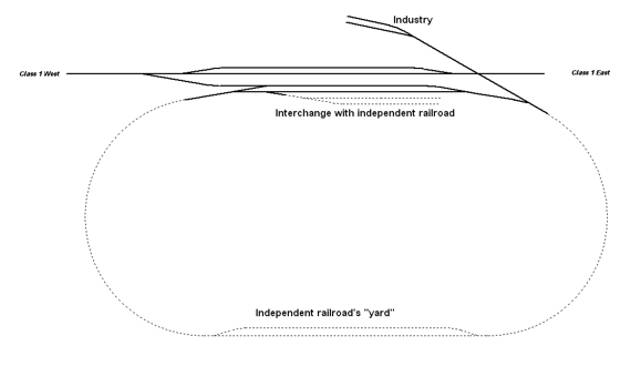

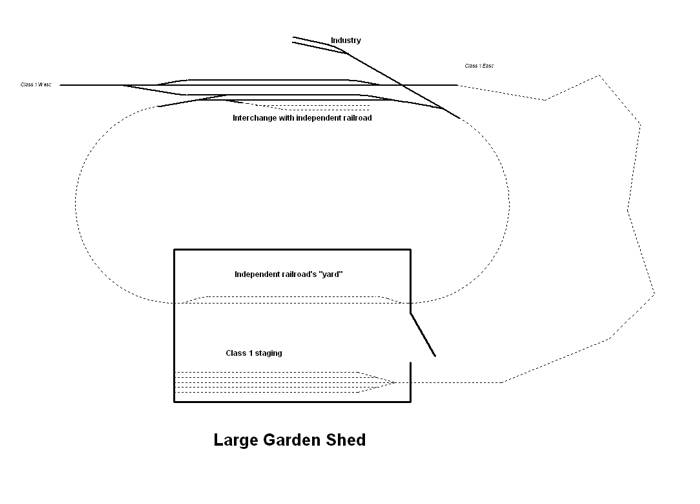

Staging - Very few model railroads depict an isolated part of the continent’s rail network, so most of our layouts should provide for moving traffic between our railroad and one or more other railroads that connect end-to-end with it or cross it at grade.

-

Linear design - The days of sitting in a central control pit and watching the trains go around are mercifully over for those who enjoy operation. But even linear, walkaround designs can be compromised by having a track cut through the base of a peninsula, keeping the engineer from following the train.

-

Walkaround control - Any layout design that doesn’t accommodate walkaround control as a means for the engineer to follow alongside the train needs to be rethought. Command control has made walkaround operation much simpler to achieve. Radio and infra-red wireless throttles, which avoid “plug-and-chug” crew movement, are increasingly popular.

-

Car-forwarding system - You can’t “operate” unless you can simulate the work of railroading, and that means forwarding cars to their proper destinations. The Doug Smith-inspired car-card-and-waybill system still reigns supreme as far as I can tell, but today there are lots of options - both simpler and more complex (“feature-rich”).

-

Interchanges - Where railroads cross at grade, they usually construct interchange tracks so they can deliver cars to and receive cars from each other. An interchange track is often a quarter circle, more or less, in one quadrant of the level crossing. Since almost any type and quantity of car can be found on an interchange track, for us it’s effectively a “universal industry” that offers more traffic variety than any other industry. Bonus: There are no industrial structures to build.

-

Large industries - It’s tempting to model a variety of smaller industries, but in so doing we often build industries so small that they’d be lucky to fill one semi- trailer a week, let alone several boxcars or covered hoppers per day. It’s often better to model one large industry that can generate a lot of rail traffic using a variety of rolling stock. Some examples would be a glass or tire plant, a brewery, or a paper mill. These are typically big complexes with many structures, but most of the buildings can be depicted as flats or assumed to be located out in the aisle off the end of a truncated spur track.

-

Switching - While I’m often found dispatching or out on the local, I lean toward more visceral jobs such as getting a heavy train up a long grade without doubling the hill. But I do appreciate the intellectual challenges and rewards of yard and industrial switching. Most modelers seem to prefer a lot of switching, and several veteran operators have recently built layouts that focus on industrial switching and yard work. Building-in lots of yard and local work is therefore a priority for most operators.

-

Traffic control - Small layouts can get by without a dispatcher and/or train-order operators, but these are typically the most realistic and challenging jobs on the railroad - especially now that timetable-and-train-order operation is back in vogue.

-

Branch or short line - A connecting rural branch or short line offers a chance to use older, smaller motive power (see photo) while offering low-key operation for those who don’t want to deal with the intensity of the main line.

-

Sound - Once a novelty, then nice-to-have, sound effects are now a must for many modelers. The realism Digital Command Control (DCC) sound imparts is phenomenal, and operators now use whistle or horn signals to support operations such as sending out a flag or alerting a train being met or passed that another section is following.

I’d be interested in a discussion of the top ten for an outdoor railroad, as I don’t think they’re the same as those listed above.