An excellent presentation by National Geographic on the evolution of the first railway locomotive.

Enjoy…

An excellent presentation by National Geographic on the evolution of the first railway locomotive.

Enjoy…

Great film! Thank you for sharing. Time to go out and fire up the “Clishay”. No special history involved, but inspiring.

Randy, Thanks for putting that show out there. It is very interesting and entertaining. So… the Rocket was actually the first reliable and useful steam locomotive. The Cass Scenic Railroad (a great terrific destination for any steam railfan) operates the Durbin Rocket, a 2 hour excursion trip, along the Greenbrier River using a fully restored Heisler #6 locomotive. I have wondered why the name Rocket. Maybe from it’s early predecessor in England? …Mark

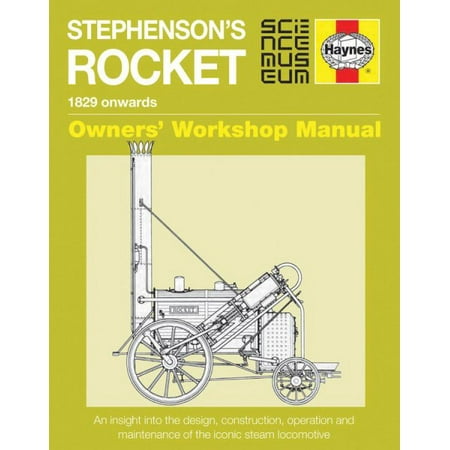

For Xmas last year I was given a book on “Rocket” done in the style of an auto maintenance book. You know, chapters on background, how it works, how to drive it, and where to find one.

The latter surprised me. The much-modified original (it had a long life) was taken apart by the Science Museum a few years ago as an archeology study, and put back together. They built a working replica which has a modern boiler so it can be used. The Ford museum in Dearborn had several replicas built, and one is still in Michigan. And there was at least one earlier replica that didn’t work very well.

Double post

Mark Betlem said:

So… the Rocket was actually the first reliable and useful steam locomotive.

A bit about its place in history: http://www.rainhill-civic-society.org.uk/html/newrainhillHistory.html

A competition was to be held at which the best designs would be tested. The site of the Trials, as they became known, was a completed section of level line at Rainhill, 9 miles from Liverpool. Locomotives were brought by sea to Liverpool, assembled there and carried to Rainhill by horse-drawn wagons. Only three serious contenders reached the starting line on October 6th, 1829. They were Timothy Hackworth’s “Sans Pareil”, Braithwaite and Ericsson’s “Novelty” and Stephenson’s “Rocket”.

The trials were held before a vast concourse of spectators and the atmosphere was like that of a race meeting. Grandstands were erected alongside the tracks (just as they were to be 150 years later when visitors from all over the world came to for the “Rainhill 150” celebrations). The clear winner was Stephenson’s “Rocket” which hauled a specified load 40 times over a distance of one and three-quarter miles and, in fact, reached a speed of 30 miles per hour. Rocket also demonstrated its ability to climb the nearby Whiston incline unaided, proving that static winding engines were unnecessary.

Rocket’s design proved to be the only one at the trials which could be successfully developed further and its principles were embodied in all subsequent steam locomotives.

The railway was finally opened by the Duke of Wellington on September 15th 1830. It was the first full scale inter-city railway exclusively powered by locomotives and providing a service for both passengers and freight. Its double track throughout and its strict timetable formed the prototype for subsequent railways throughout the world.

Mark Betlem said:

So… the Rocket was actually the first reliable and useful steam locomotive.

The book I mentioned [“Owners’ Workshop Manual: Stephenson’s Rocket - 1829 Onwards by Gibbon Richard”]

has much more info than I had read before. There’s one section describing the operation of excursions out of Liverpool as the rest of the railway was being built. After Rocket won the trials, it hauled the curious locals up hill and down dale to show what this new-fangled invention could do.

There were many other steam engines built and running by then - the Stourbridge Lion was already in Honesdale, PA, and had proved too heavy for the wooden track. Rocket’s claim to fame is that it was the prototype for all modern steam engines. Multi-tube (flues) in the boiler, a blastpipe to encourage the fire, and cylinders in line with the center of the axle driving them directly. Shortly after Rainhill, it was rebuilt with the cylinders much lower and more horizontal, making it even more like a modern engine, which is how it looks these days in the Science Museum.