Yankee Girl Mine, Poughkeepsie Gulch, Red Mountain District, San Juan Co., Colorado, USA

Latitude & Longitude (WGS84): 37° 53’ North , 107° 39’ West

Latitude & Longitude (Decimal Degrees): 37.8833333333 , -107.65

Latitude & Longitude (Degrees plus Decimal Minutes): 37° 53’, -107° 39’

credit: U.S. Geological Survey

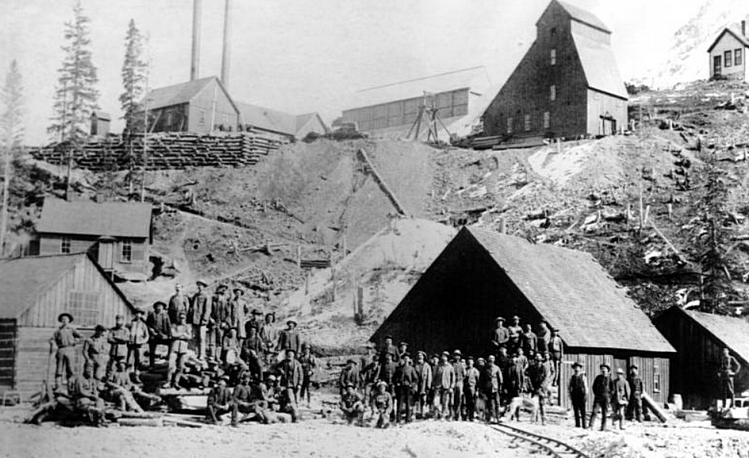

On Aug. 14, 1882, prospector John Robinson, out hunting in the rarefied air, exhausted from climbing up the steep slopes of Red Mountain, sat down to rest. He spotted a piece of rock. When he picked it up, he noticed that it was unusually heavy, a sure sign that it was mineralized. Robinson broke the piece in half and saw a silver-gray metallic mineral called galena, typically composed of a mixture of lead, silver, and other metals. Realizing this was a rich find, Robinson began to search for the source of the galena. He soon found an exposed vein and claimed it in his name and those of his partners, Andrew Meldrum, A. E. “Gus” Lang, and August Dietlef.

Robinson returned with his partners to determine the extent of the claim and the men dug a shallow shaft a dozen feet deep. Much to their delight, they dug through solid metallic ore extending the width of the shaft. As a precaution, they staked claims on all four sides, as the ore body seemed to have no limit. Of these claims, the Orphan Boy and the Robinson became major silver producers, but their original discovery, the Yankee Girl, drew the greatest attention to the Red Mountain district.

It turned out that the men had hit the top of a vertical shaft, a chimney, of solid ore, a rare occurrence in the mining world. The prospectors dug out 4,500 pounds of ore, placed it in sacks, and sent a long pack train down to a smelter in Ouray. The mill produced an average of 88 ounces of silver per ton. More than half of the ore was lead, which was valuable to smelters for use as flux.

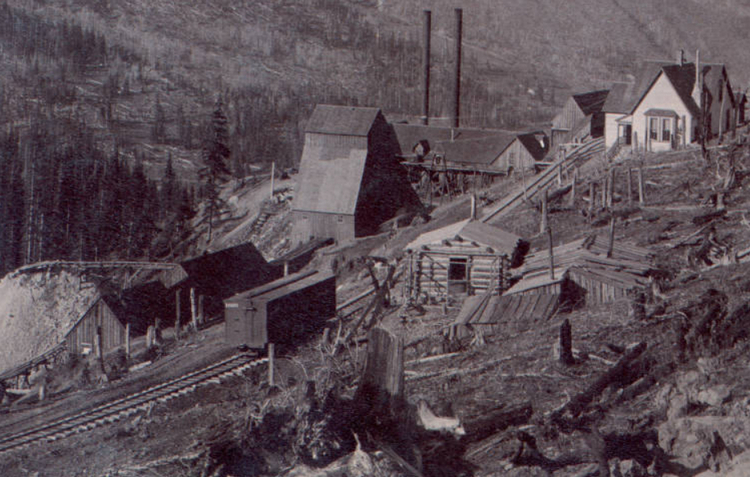

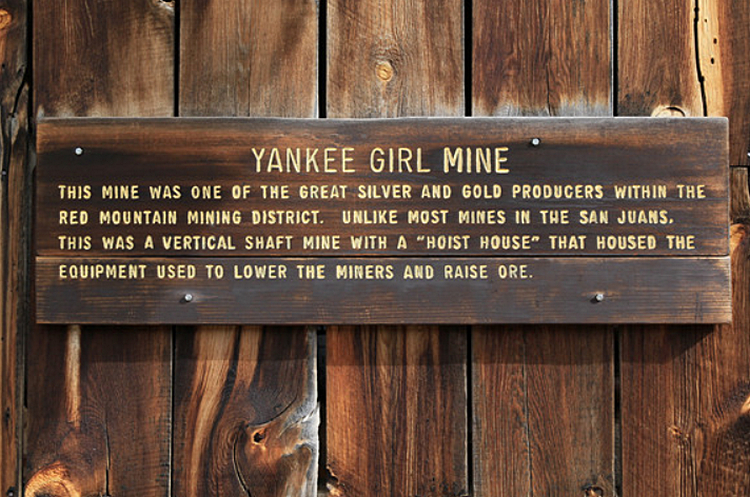

The Yankee Girl shaft house above the mine has a bull wheel and wire for getting out ore. The mine produced silver, copper, and gold, about $8,000,000 worth in its time. There were problems; digging caused water to fill the shafts. They bought a $30,000 pump to keep the water out, but corrosive water eroded the pump in just one month.

In 1883, the Yankee Girl was joined with the Robinson and Orphan Boy mines by interconnecting tunnels. Eventually, these tunnels reached a length of 25 miles. A boarding house was constructed at the Yankee Girl for the miners. The mine was sold for $125,000 (worth about $2.5 million in today’s dollars), giving the men enough money to finance development of their other mines.

credit: Kenneth Jessen (edited)

Mining created the need for a town. Gusto, Colorado, located at the foot of Champion Gulch on the Silverton Railroad line, formed around the workings of three large mines; the Guston-Robinson, the Yankee Girl, and the Genessee-Vanderbilt. The Guston post office was established on January 26th, 1892, and closed on November 16th, 1898. An English preacher, a Rev. William Davis, succeeded in establishing a church in Guston in 1892. (He had been unsuccessful in establishing one in Red Mountain Town.) The day the church was dedicated in Guston, a fire in Red Mountain destroyed the town’s commercial district. More than one resident of Red Mountain questioned the connection to divine intervention. The church at Guston not only had a bell, it also had a steam whistle to signal miners that services were about to start.

Guston declined rapidly after the Silver Panic of 1893. The effects of later sporadic workings and recent environmental cleanup have removed any traces of residences, although the shaft house of the Yankee Girl, and a few remains of the Guston-Robinson mine still stand.

credit: Jerry Clark (edited)

Yankee Girl mine. — The Yankee Girl ore body was discovered in the autumn of 1881 by John Robinson. In 1882 it was being opened by two shafts, each about 50 feet deep. At that depth the ore is. said to have been about 9 feet wide, consisting chiefly of galena with bunches of chalcopyrite, and carrying as much as 80 ounces of silver and 6o per cent of lead. The ore body was rapidly opened up and proved large and rich. In 1883, with a thousand feet of drifts and shafts, about 3,000 tons of ore were extracted, with an average value of nearly $150 per ton. The product for this year is given in the Mint report as $400,000, and the ore is said to have carried a high percentage of lead. In 1884, according to the same authority, the mine was producing about 40 tons a day, which, at $150 per ton, would be something over $2,000,000 for the year. This, however, is obviously an excessive estimate. In 1887 the output is not known, but was probably much less than $200,000. In 1890 it is credited with $1,352,994, the silver, as usual, being given at its coinage value and no return being made for copper or lead. In 1891 the product is given as $601,465 in gold and silver, and in 1892 it had fallen to $95,445. Of this amount $5,200 was in gold, $48,333 in silver (coinage value), $3,632 in lead, and $38,280 in copper. Thus these fragmentary records show that in the course of ten years’ working the ore changed, within a vertical distance of 1,000 feet, from one carrying chiefly galena to one rich in copper. This has probably been the most widely known and most productive mine in the Red Mountain district, although closely rivaled by the Guston. But it was an expensive mine to operate on account of the irregular form of its large ore bodies, the abundance and corrosive activity of its waters, and the necessity of hoisting and pumping through deep shafts. These adverse conditions, in conjunction with a falling off in the value of the ore caused the mine to shut down about 1896. …

At present the Yankee Girl shaft is about 1,050 feet in depth. A plan of the extensive levels shows an intricate maze of workings in which no linear system is discernible. The mass of the workings lie just west of the shaft, and in plan may be roughly inclosed in an irregular triangle. A smaller extent of workings lies just east of the shaft. Inspection of the dump, as well as inquiry, shows that there was never much vein quartz associated with the ore. The “quartz” of the miners is very largely the bleached and silicifled country rock adjacent to the nearly solid bodies of ore. Where vein quartz occurs it usually carries iron pyrite. Barite, in small masses and crystals, occurs embedded in the bornite. The chalcocite is generally inti mately associated with small amounts of chalcopyrite. Some speci mens show that the ore has been fractured and recemented by veinlets of calcite. The ore minerals observed on the dump were galena, sphalerite, chalcocite (stromeyerite), bornite, chalcopyrite, and pyrite. Cosalite was recognized in 1884, therefore, in the upper part of the deposit…Proustite and polybasite also occurred occasionally in the Yankee Girl ore bodies. All accounts of the Yankee Girl mine unite in emphasizing the chemical activity of the underground waters encountered in the workings. According to Schwarz they contained “24 grains per gallon of sulphuric acid (SO3).” Candlesticks, picks, or other iron or steel tools left in this water become quickly coated with copper. Iron pipes and rails were rapidly destroyed, and the constant replacement of the piping and pumps necessary to handle the abundant water was a large item in the working expenses. All agree in stating that the water entered far less abundantly below the sixth level. Some who worked in the mine express it as being " not so bad" below that level. But closer inquiry usually elicits the information that it was less abundant but as much or even more corrosive than at the upper levels.

The product of the Yankee Girl is roughly estimated at about $3,000,000.

credit: report pictured above, 1901